Opinion: The Australian delusion: the lameness of sameness

By Mark Kenny

A version of this article was originally published by The Canberra Times.

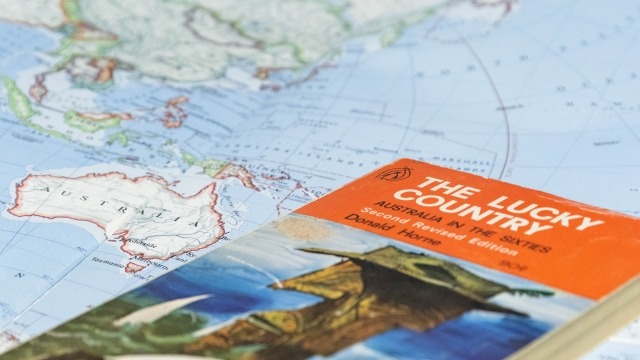

WHEN Donald Horne finished writing “The Lucky Country”, he was barely two decades younger than the new nation he described.

His confronting 1964 book was a publishing revelation, dense and yet popular to a degree that no Australian non-fiction book had been. It remains in print today.

The passage from which it drew its widely cited title did not appear until the final chapter: “Australia is a lucky country run mainly by second rate people who share its luck. It lives on other people's ideas, and, although its ordinary people are adaptable, most of its leaders (in all fields) so lack curiosity about the events that surround them that they are often taken by surprise”.

Even among the minority who read the whole paragraph, there was an overly physical take-out which Horne was always keen to correct: “I didn't mean that it had a lot of material resources … I had in mind the idea of Australia as a derived society whose prosperity in the great age of manufacturing came from the luck of its historical origins … In the lucky style we have never 'earned' our democracy. We simply went along with some British habits”, he wrote a dozen years later.

Last week, academics from many disciplines including historians, linguists, demographers, economists and lawyers, gathered in Canberra for two contiguous symposia marking the 60th anniversary of Horne’s landmark national assessment – one led by the Australian Studies Institute and the other by the Australian Academy of the Humanities.

Across the three days, scholars weighed Horne’s acerbic critique, noted some glaring omissions, and measured his underlying assumptions against changes in economy, social attitudes and historical knowledge since.

Amid many powerful insights, I was struck by two that spoke to a very contemporary Australia-and-the-world experience.

Frank Bongiorno used a keynote address to posit that a uniquely Australian simplification of equality – often valorised as “mateship” – had mixed with low levels of historical and constitutional literacy to enable the skewering of the Voice in last year’s referendum.

An ANU Professor of History, Bongiorno reminded us of Horne’s observation about Australian sameness.

“…most Australians,” wrote Horne in his first edition, “are bereft of feelings of difference; they think that all people are the same, that what is good for oneself is good for anyone else … They seek similarity where often it does not exist – even among themselves. They reach out for the essential humanity of man but the apparatus with which they do it is too primitive for the task. They retreat into suspicions”.

Bongiorno juxtaposed Horne’s description against the findings of researchers at ANU’s Centre for Social Policy Research (Polis) who had surveyed “no” voters to ascertain their motivations for disagreeing with the Voice proposal’s goal of improved national unity.

“Australians voted no because they didn’t want division and remain sceptical of rights for some Australians that are not held by others,” the Polis researchers had concluded.

In other words, the Voice came to be seen as a divisive mechanism for eroding equality by delivering “special” rights. Understood this way, it fell foul of an idiosyncratically Australian construction of equality founded in the ahistorical Arcadia of sameness. As a coherent justification for voting “no”, one either had to wilfully disavow knowledge of frontier wars, dispossession of lands, rape, slavery, massacres, child removals, and economic disadvantage, or to have considered them irrelevant. One also had to put out of mind present-day realities that are the subject of repeated media exposure in the annual closing the gap report. Perennial problems like reduced life expectancy, chronic disease, illiteracy, endemic poverty and unemployment, incarceration and deaths in custody.

A sullen year after the Voice failed, Bongiorno’s contemplation offers a plausible account of how the Coalition’s mischievous claim that the Voice was “divisive” worked to flip its unifying intent and licence Australians to say no.

From Julianne Schultz, there was the observation that while Horne’s book was not predictive, its publication happened for a reason. Professor Schultz argued there was a palpable sense running under Horne’s commentary that 1964 was a “hinge” year, a turning point where the past was yielding to a changed reality, here and abroad.

The 1960s was a turbulent decade. It saw the explosion of violence in the US, assassinations, demonstrations, an insistent new feminism, vast politico-cultural outputs, civil rights, anti-war and flower-power movements and a flourishing of fresh democratic potential. Australia, too, would feel these rising thermals but in 1964, they were less apparent.

Sixty years later, Schultz senses that epochal atmosphere again, although in 2024 the expansive hope and possibility of the 1960s has been “trumped” by vengeance and foreboding.

Neo-liberal democracy feels exhausted and clueless, its globalist promise, betrayed. Millions have been left behind. Social and environmental movements are in retreat even as the planet hits an environmental tipping point. Violent wars and new military alliances mock the multilateral architecture. Strongmen proliferate. A coarse new “bro-ligarchy” calls the shots.

If Horne were alive today, he’d be just another voice to be shouted down. Still, I imagine he would look at our feckless flag, the Voice rejection, AUKUS and the risible debate over Kevin Rudd, and decree that if we want any new luck, we best start making it ourselves.

Mark Kenny is the Director of the ANU Australian Studies Institute and host of the Democracy Sausage podcast.